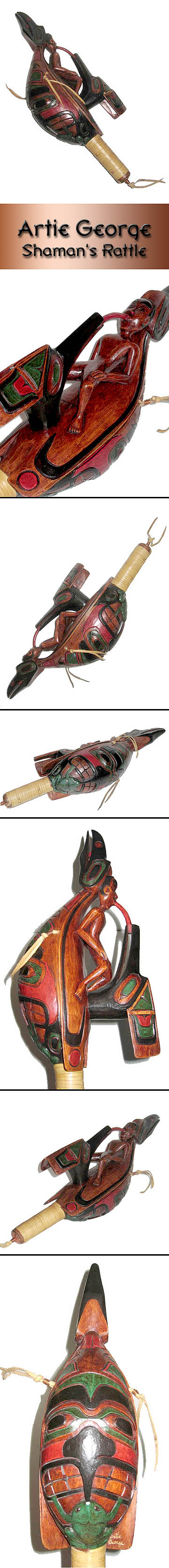

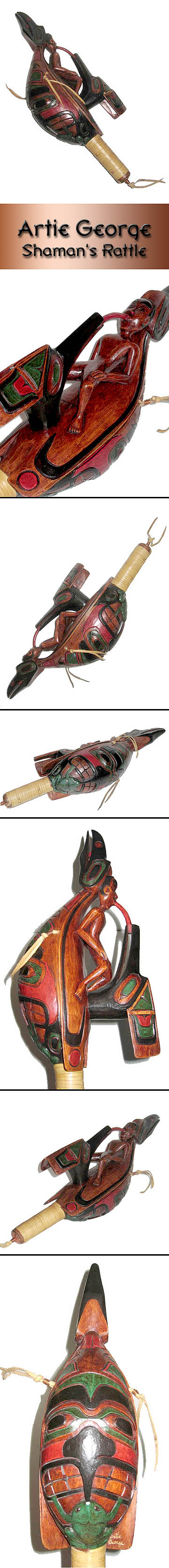

Artie George

Shaman's Rattle

18 1/4"

L x 4 1/4" W

Artie George is a Coast Salish

wood carver. Born in North Vancouver in 1970, he is from the

Tsleil-Waututh Nation (Burrard Band). He is the grandnephew of

the respected actor, author and raconteur Chief Dan George.

Self-taught, Artie's fifteen

years of experience dedicated to his art has awarded him respect

from his peers as a carver of fine detail. Through his art, Artie

George expresses visually what his great-uncle embodied in the

words and deeds of his life; the face of our own humanity, at

once with nature and the great spirit within.

He participates in aboriginal

events and major, juried craft shows such as the Circle Craft

and Out of Hand Exhibitions. His works are found in the Glenbow

Museum in Calgary and the University of British Columbia Museum

of Anthropology.

Northwest Coast rattles are

finely sculptured percussive instruments that are employed to

communicate with the spirit world. The high, light, swooshing

sound of a thinly carved hardwood rattle is known to attract

benevolent spirits, and is often used to accompany spiritual

songs that call on the spirits of ancestors to aid in times of

transition or crisis.

The Tlingit name for the raven

rattle is Sheishoox, a word that imitates the sound of the instrument.

Certain kinds of rattles are the exclusive property of shamans,

used in their specialized kinds of spirit communication, while

others are employed by clan

and family leaders in sanctifying a ceremonial space or gathering.

Shaman's rattles in the north

were most often globular in form, or among the Tlingit, the oystercatcher

rattle was the type used exclusively in shamanic practice. In

the Central Coast Salish region, the sheep horn rattle was the

type created for ritualistic use.

Perhaps the most graceful

and delicate object created by Northwest Coast ceremonialists,

the Raven rattle is also a very old and respected object of tradition.

Certain extremely old and brittle ones exist, likely collected

from graves, which suggest that the image usually portrayed is

one that is very ancient, though its specific origin is unknown.

This arrangement of raven,

human, and sometimes frog has been reinterpreted by successive

generations of artists, most of whom leave the core image absolutely

intact, while rendering their own unique variations of the details

thereon.

This example bears the most

common raven rattle features: the form line face with a received

beak on the belly, the tail of the raven raised up and elaborated

into a long-beaked bird face, and the reclining human figure

with its tongue held in the beak of the tail-bird.

In this version, the tail

is set more forward on the raven¹s body than on many others,

and the body and legs of the human are correspondingly short.

The face of the human is handled as a softly-arched, formline-type

structure, the features of the face quite shallowly relieved.

The head of the raven has

been cut through up the middle, isolating the neck and opening

a space between the ears. This traditional structure harmonizes

with the delicate piercing on the back of the raven, and removes

unwanted weight from the wood which may affect the rattle¹s

sound.

The flat design embellishment

is of an early style. A rattle such as this would have been held

by a succession of high-ranking chiefs of clans at ceremonial

gatherings as a symbol of wealth and prestige, as an accompaniment

to songs and dance.